The Elector’s Musical Inventory

It’s a testament to the musical leanings of the elector that he kept an extremely detailed inventory of the scores in his musical library, which still exists today and is held, along with other musical scores, in the Biblioteca Estense Universitaria in Modena under the shelf mark “Catalogo Generale 53, I-II” (for simplicity’s sake, it will be referred to here as “Catalogo Generale”). The original binding, and probably also the title page, have been lost, but at 640 pages and containing entries on a staggering 3400 works, the inventory is one of the most detailed sources in existence for the active musical life in Bonn.

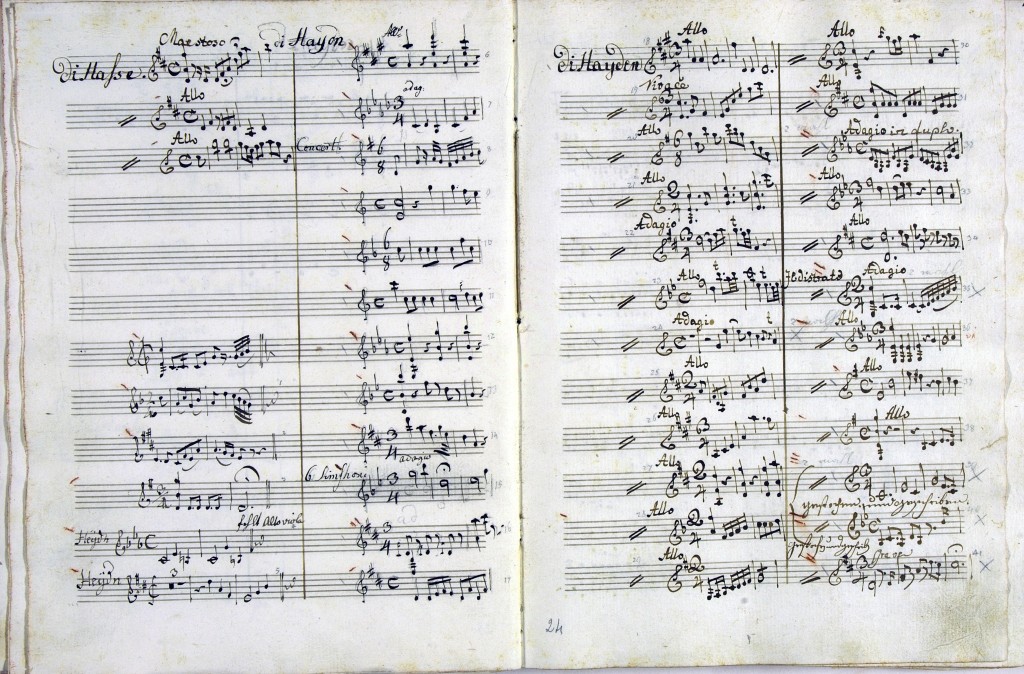

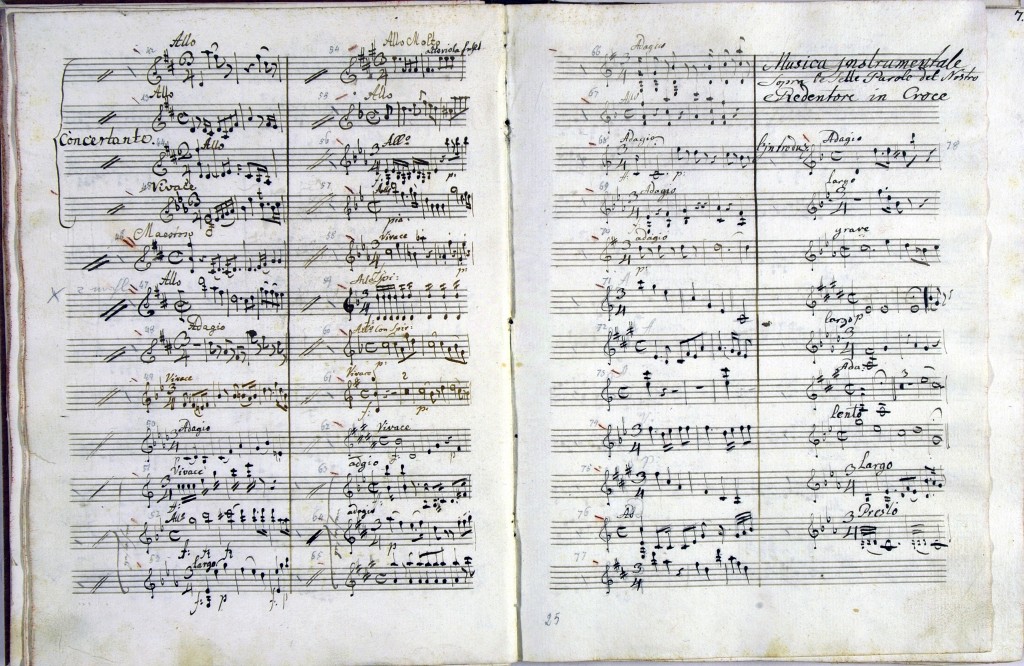

Beyond this, what makes the Catalogo Generale special is the care put into its preparation. It uses the same high-quality Italian handmade paper that appears in Viennese musical manuscripts of the 1780s. For all instrumental works, a musical incipit is given, a rare luxury for such an inventory which must have required precious time on the part of a professional copyist, who would have had to first retrieve the score or parts, notate the first few measures in full, and then retrieve the next score.

On the first page of the musical listings (folio 2r), a few measures each from seven symphonies by Carl Friedrich Abel (1723-1787) are carefully copied out in a fine copyist’s hand.

This fine paper also helps to date the manuscript, since the watermark for most of it is identical with paper Mozart used in autographs dated 1784. This might suggest that Maximilian Franz commissioned the Catalogo Generale shortly before he left Vienna to become elector. The inventory is laid out first by genre, and within each genre alphabetically by composer. By the different layers of handwriting throughout the volume, as well as the dates of the individual compositions, it’s clear that the elector continued updating the inventory as he received new pieces. The earliest titles date from before his move to Bonn in 1784, and the latest ones from after he fled from the French in 1794, which suggests that he held on to it until his death in 1801.

A Fascinating Historical Document

The Catalogo Generale is a rich source of information, as it represents a tremendous cross section of what music was heard and played in the late 18th century. It also is an important documentation of the lines of communication between composers, publishers, and the music collectors among the nobility. For instance, it is well known that Max Franz sent Beethoven to study with Joseph Haydn, and that Haydn even visited Bonn on his way to London in 1792. The elector also was apparently an avid collector of Haydn’s symphonies, as witnessed in the four pages in his inventory devoted to them.

On these four pages (folia 23v-25r), three different sets of handwriting can be distinguished in the musical incipits. To complicate matters further, there is another layer of numberings in pencil and in red crayon (Rötel), made at some point after the entries were finished.

Notwithstanding a few duplicate entries and a few works which we now know to be spuriously attributed, a total of 71 orchestral works by Haydn were in Max Franz’s music library, including an almost complete set of Symphonies Nos. 32-92. Astonishingly, on the third and fourth pages, the symphonies 85-92 (numbered in pencil 63-70) appear exactly in the order they were composed. Musicologists 200 years later would still struggle with the true chronology of Haydn’s works. Perhaps this would suggest that Max Franz (or someone else at court) at some point had a direct link to Haydn and was able to acquire the works when they were brand new? That the court musicians would have played many of these symphonies lends some credence to the famous anecdote surrounding Haydn’s 1792 Bonn visit, as the elector introduced the then-famous composer to his musicians with the words, “Thus I make you acquainted with your much cherished Haydn.”

A Barometer of 18th-Century Musical Taste

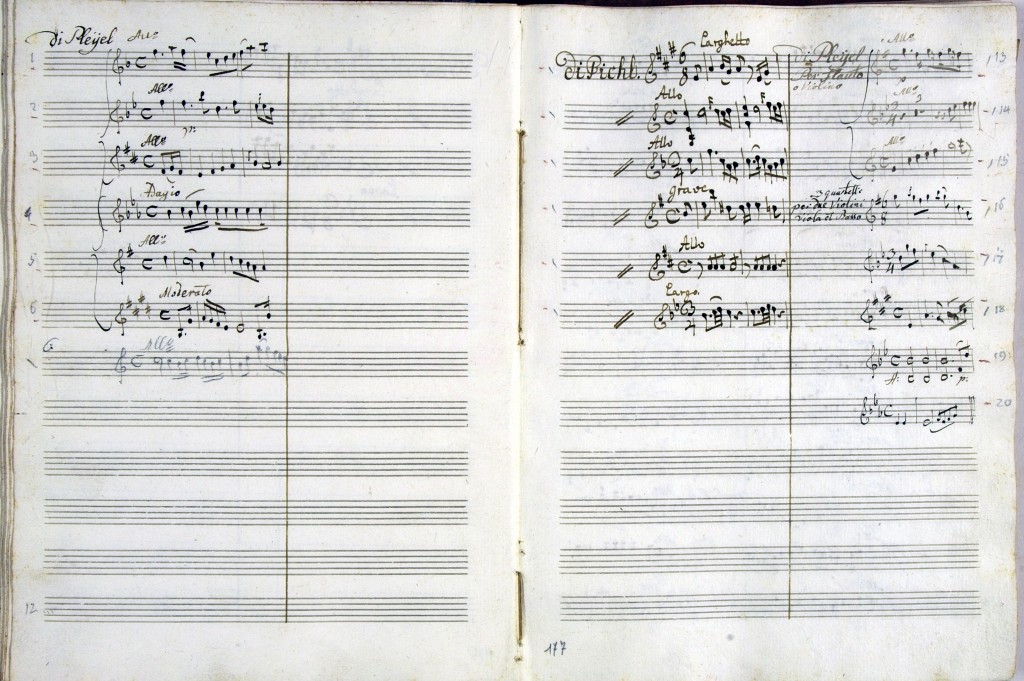

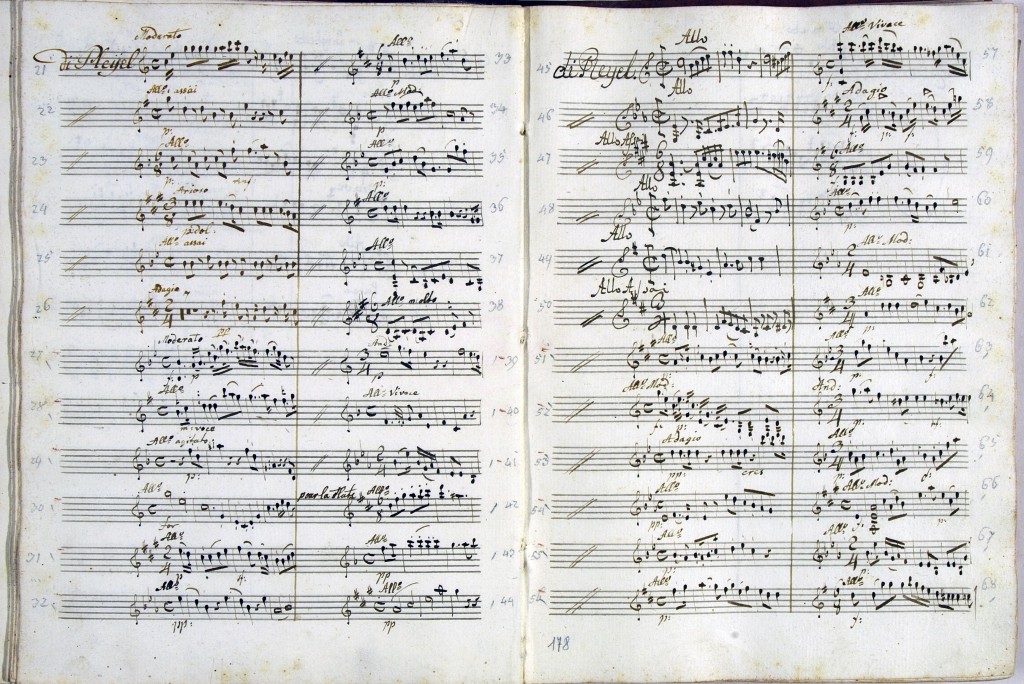

This is not to say that only Haydn’s music is well represented in the Catalogo Generale. In fact, the breadth of composers represented, most of whose names are only still known to specialists, makes the inventory for us today an excellent barometer of what music was widely circulated in late-18th-century Europe. To take another example, Ignace Pleyel (1757-1831), better known today as a music publisher, was unbelievably prolific as a composer as well. The Catalogo Generale contains so many of his string quartets that the page that was originally allotted for them ran out. The fourth page below was originally the first layer of entries (retrospectively numbered 45-68), after which a second scribe entered further works on the previous page. Then once this page ran out, the same scribe had to flip back further, to the first and second pages shown below. The latest entry appears to be the one in pencil on the first page below, from a C-major quartet first published in 1791. The two quartets immediately preceding it (in G and E major) were however first published in 1792. Another candidate for the final entry might be the last one on the following page (pencil number 20). While this quartet dates from 1788, the incipit is in a third handwriting (recognizable by the different form of treble clef), which in other parts of the inventory appears for the latest works.

On these four pages (fol. 176v-178r), 63 string quartets and 5 quartets for wind and string instruments by Ignace Pleyel are recorded. By the dates of the works and the handwriting, it’s apparent that the list was first begun on the fourth page and then continued backwards page-by-page until the latest entries on the first page, made after 1792.

Our view of music history is very often shaped by the tastes of later generations, who would canonize the works of certain composers, whose music is continually played to this day on concert programs. But this process of canonization also erased from public memory the work of many others. This is why historical documents such as the Catalogo Generale are so important. They represent music history without the particular tautological filter that we, as inhabitants of a future age, can’t avoid imposing on it.

* * *

For more information on this inventory, see the excellent article by Juliane Riepe, “Eine neue Quelle zum Repertoire der Bonner Hofkapelle im späten 18. Jahrhundert,” in Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 60/2 (2003), 97-114.